Risk is an interesting concept within the fire service that is loaded with emotional, philosophical, and tactical tension. Risk has been the centerpiece for many heated discussions within the fire service. On one hand, we have a totally risk averse group of firefighters in which their generation was told that “they themselves come first”, “our safety is most important”, and that “everyone goes home”. For this group, aggressiveness on the fireground is synonymous with recklessness. However, our service demands calculated risk, not fear-driven hesitation.

You cannot completely disregard safety, and just “Leroy Jenkins” it through the front door without any thought process behind what you are doing. Aggressiveness without intelligence is just recklessness. Aggressiveness is essential to being an effective and winning fireground force. Aggression has a purpose and should be sensible. An aggressive firefighter is someone who conveys precision, is well trained, and acts with assertiveness. The people who call you, want you to be default aggressive. They need confident firefighters, they need people to go find them. Time is our enemy. Our profession demands calculated risk because the public expects us to act decisively and at a high level to save lives. If your kids were in that room, would you want a crew willing to take that calculated risk to save them? I already know your answer.

What is Risk?

Risk is a relative term, it is subjective and different to each individual. The action of risk is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as: to “expose (someone or something valued) to danger, harm, or loss.” We often hear the phrase “risk a lot to save a lot.” Well, what does that even mean? We can go around the room and have a number of different definitions of what that is. Everyone can look at the same thing and have varying opinions on the risk level or the risk assessment. So risk in our profession has almost no definite definition.

Our job is inherently dangerous, but to me knowing that I have bunker gear and training and other equipment and experience at my disposal and then I look at what our victims have, nothing. The risk has already been relatively small to me compared to the civilian. Again, they’re unprotected they have nothing but the shirt on their back, they don’t have the time that we have when we enter that space. Yes it is true, that you can do everything right on this job and something bad can still happen to you. But, you can also do everything wrong and have zero consequences. That’s where many have grown complacent.

The risk is calculated with experience, knowledge, training, our instincts, and courage. The fire service understands the risk of death for our unprotected civilians, yet the same outcome continues due to fear driven decisions.

“The risk that scares people & the risk that kills people are very different”-Peter Sandman.

There is no such thing as “We will risk nothing”, there is risk in just about everything we do in life. The tones simply going off is putting us at long term risk for heart issues, but without having an alert civilians would die and their property would not be protected. The fire service must carefully manage its mindset, culture, and training, as these directly impact the outcomes for civilian lives and property. If the fear of risk dominates, the fire service will fail to meet public expectations—leading to a loss of trust, reduced funding, and ultimately, the collapse of the service itself. Which will lead to a “no risk fire service”, because there won’t be one.

Even after considering all the known hazards and putting measures in place, there will still be residual risk. Residual risk comes from two main places: We can’t know everything, so the unknown is always a hazard that you are exposed to. Secondly, there are some things that you can mitigate but can’t remove entirely. Before we have a real conversation about what we are willing to risk, we must know what the mission is. If the mission is to save a life, then we do what we can to control the hazards but we keep moving forward.

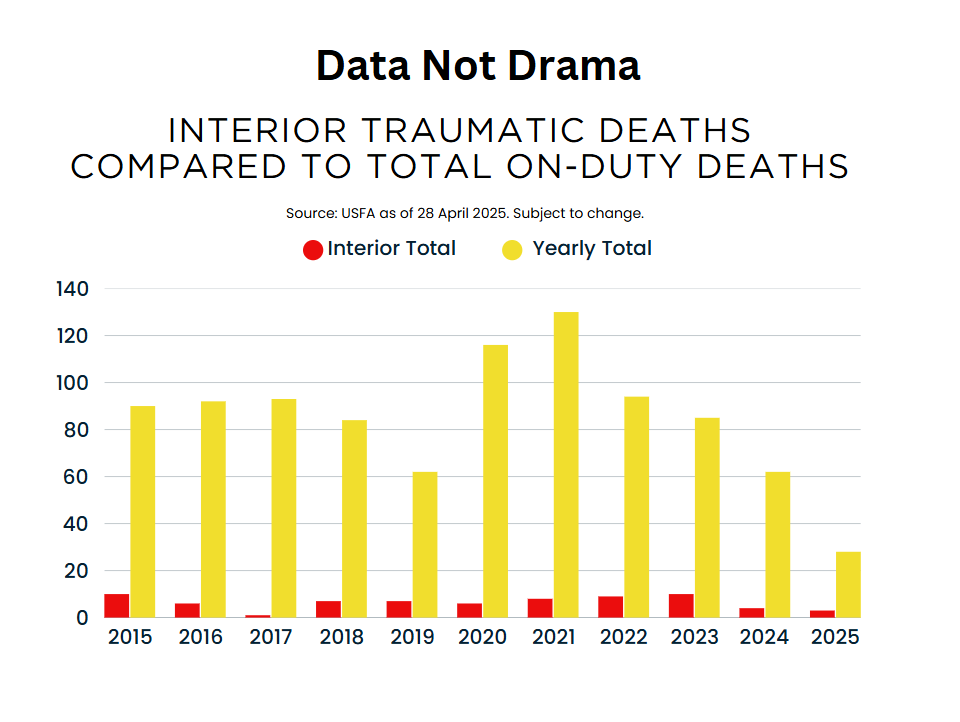

The reality is that our job is not really as dangerous as we make it out to be. Over the last 40 years, firefighter line-of-duty deaths while operating inside a structure fire have decreased by more than 80%. The death rate for firefighters operating inside structure fires is 7.6 firefighters per one million fires. Over the last 40 years, the civilian fire death rate for one- or two-family homes has increased by 34%. The most recent data reports that rate at 1 civilian fire deaths per 100 fires with the trend rising. That’s a difference of four orders of magnitude. Let’s be clear: the fireground isn’t as deadly for us as we make it out to be. If we truly care about firefighter safety, we should focus on what kills us most—cardiac events, cancer, suicide, and vehicle accidents—not on using safety as an excuse to avoid fulfilling our duties.

There is a significant difference between risk avoidance and risk mitigation. In the fire service, we often confuse discussions about risk with what are actually conversations about uncertainty. We acknowledge the inherent risk that comes with our occupation. We accept and reduce those risks with our preparation and competency accomplished through training, our equipment, our mindset, and our experience.

Training reduces risk

Education reduces risk

Water reduces risk

Searching early reduces risk

Discussion reduces risk

Calculations of unknowns and emotions don’t reduce risk

“Attempting to make your job safer by teaching you to place yourself above those in need is wrong and goes against everything the fire service has ever stood for. We have the highest approval rating and respect of any profession. Why is that? Because we do what has to be done, we are noble, we are self-sacrificing, we are willing to risk our lives to save a total stranger. When we modify or tweak that thinking along the lines of saving lives, we not only risk the fall from public grace, we risk something much more harmful, the loss of our identity. There are many tasks you perform every day that are not fire related, but only firefighters put out fires. When that parent meets you outside their house and tells you their child is inside trapped, you are their last hope. What are you going to do? You must find a way in, to save that life if humanly possible. What are your chances? Your chances are always the same, they’re 50-50. Either you do it or you don’t. You must call upon what’s inside you, your courage, your determination, your will. You must shed your personal cocoon of safety and take a risk. If it was easy someone else would have done it already. Let’s not let them down. They’re all we have.”

-Lt. Ray McCormack FDNY

The Other Side of The Coin: Risk to Civilians

Every year approximately 4000 Americans lose their lives due to fires in this country. We are their last and only hope. When we respond, “their emergency is our emergency.”

Our public recognizes their risk from fire and pays for our service to reduce their risk, they expect us to keep their families safe. Civilian lives are lost in situations where the perceived risks were not justified. Departments that adopt a mindset where phrases like ‘Everyone is out’ or ‘No one is inside’ automatically alter their operations and tempo. Allowing fear of injury or death to drive decisions—prioritizing perceived risk over performance, and in doing so, predetermining civilian outcomes instead of giving them a fighting chance.

” …given a fire serious enough to report to the fire department, the risk of dying in that fire has not decreased significantly over the past 40 years.”

-NFPA

Evaluating areas from the outside “That is not survivable” or defaulting to defensive operations, uses the fear of injury or death as an excuse to not perform.

Risk decisions are on each individual to make for themselves. The fire service understands the risk of death for our unprotected civilians, yet the same outcomes continue due to fear driven decisions.

“When the citizens lay their children to bed at night we are their keepers.”

-Chief Mo Davis

Search All Searchable Spaces, They Expect to be Rescued

We do not play God, it is not our job to decide who lives or die. We simply exist to give every civilian the best fighting chance. Providing every opportunity for the best possible outcome. We know from the Firefighter Rescue Survey that ~67% of victims survive, time matters, and the decisions we make on the fireground directly impact civilian outcomes. The days of survivability profiling are gone. Civilian LIFE is the primary reason for our professional existence. It is, and always will be our first priority. Firefighters should not be performing victim survivability profiling.

We decide if it’s a go or no-go, based on if the space’s conditions are tenable for a firefighter in full PPE. We must make every effort possible to occupy the space and search for victims. From the outside, we are unable to know the conditions of each room or area on the inside of the structure.

The close before you doze campaign made a promise to the public that WE WILL COME FOR THEM. Closed doors provide for isolated survivable space, certainty of this can only be achieved by completing a thorough search.

We will use our hose lines to create and take back searchable space.

There is almost no way to argue on the side of performing a “survivability profile”. Standing on the outside and judging if an unprotected civilian can survive the conditions we are seeing. Here are two fires, where two unprotected civilians WITH NO BARRIER between them and the fire were rescued and pulled out while they were still breathing.

This photo on the top is from October 31, 2018 in South Portland, Maine. A Chief and Firefighter are effecting a rescue in the fire room that we see, as this photo was taken. The Chief was applying a water can, while the firefighter was dragging the victim out of the room and a line was being stretched from the first due engine. The female survived this fire with no deficits.

This photo is from September 11th, 2016 in Milwaukie, OR. First in engine arrived to fire blowing out the alpha side all the way through the back of the house, as you can see from the glow in the picture. There is black smoke pushing from the front bedroom window that is open. The engine company made searchable space by flowing water and putting the nozzle between the fire and the bedrooms. Heavy Rescue split searched the hall, with each firefighter searching their own room, with high heat and zero visibility black smoke to the floor. A male was located in the second bedroom back, with the door fully opened. The male was rescued and had zero deficits after being released from the hospital.

The “X” Factor

I am often asked about risk assessment and making the go/no-go decision. Of course this decision is individual for each and every firefighter, training and experience factor heavily into the decision making process.

When talking about go/no-go:

We could talk about sizing up the fire.

We could talk about factoring in building construction.

We could talk about the art of reading smoke.

But then I think about the X Factor; that there could be people still in there. Trapped inside, it’s our job to go find them.

It is easy to go into information overload and cognitive paralysis when overanalyzing a structure fire or reading the smoke in depth. The fact of the matter is that this ‘X factor’ trumps all else in importance.

The people we serve trust us explicitly with their lives and are the sole providers of our occupation. It is our duty to put ourselves in harm’s way for people we do not know. This is why the public loves us. This trust was not created by any one of us, but by the generations of firemen who came before us. They fought for and earned that trust. So much so that sometimes firefighters have to give up their life. It’s up to us to uphold that trust.

None of us were drafted into the fire service—we all chose this path and took an oath willingly. That oath is a commitment, and it carries profound weight. When you raised your right hand, you made a public declaration of what you were willing to give for this honorable profession. We chose to stand in the gap—to be the bridge between those in crisis, and the help and hope they need. It’s our job to make that difference. A rescue by definition means there was a victim in harm’s way and a fully equipped trained and willing firefighter present, committed to even using themselves as an intervention between threat and Hope.

D.Y.F.J. That is why we exist. That means training with intent, showing up ready, and acting with purpose. When I am at work my priorities are the citizens. I want to train and prepare, I want to do what’s in their best interest. Every fire victim is someone’s most loved person, give them the best possible chance.

The Fire Doesn’t Care

The fire doesn’t care where you work or the size of your department.

The fire doesn’t care if you’re career or volunteer.

The fire doesn’t care if it’s your first day riding the rig as a probie or if you’re 20 years in.

The fire doesn’t care what kind of rig you show up on.

The fire doesn’t care if you’re well prepared or not.

The fire doesn’t wait—it just says GO. All it cares about is causing destruction and chaos, consuming everything in its path and trapping anyone who’s still inside.

The reality is that the moment of truth is coming. None of us know when, but at some point in your career, you’ll face a fire where lives are on the line. These calls will test you. You need to be prepared, have a plan, and be ready to execute. Otherwise, those calls will stay with you and haunt you.

“If not us then who?” – John F. Kennedy

The majority of our lives we too spend as citizens, hoping on the fire department to come save us and our loved ones.

The Story of Tom and Pam Price

The remarkable survival story of Tom and Pam Price serves as a stark reminder of why survivability profiling—deciding who is worth rescuing based on perceived odds—has no place in fire service operations. On the night of May 30, 2015, Tom and Pam’s home in Muncie, Indiana, was consumed by a raging fire with heavy involvement upon arrival. The fire department made the initial decision to go “defensive,” due to the volume of fire and fear of collapse.

Despite overwhelming evidence that the Prices were still alive and trapped inside, the determination of a 911 dispatcher to keep Pam on the phone proved crucial. After three desperate 9-1-1 calls pleading for help, begging crews to enter. 35 minutes into the incident, firefighters re-entered the structure, against all odds, and found the Prices alive, severely burned but conscious.

This miracle highlights the fallacy of survivability profiling—the practice of assessing the likelihood of survival based on factors like fire conditions, building construction, and the perceived time frame for rescue, and then making decisions on whether to attempt a rescue. When we assume who can or can’t be saved, we disregard the human factor—the resilience, will to survive, and the potential for external factors to change the course of events.

Whether you believe in God or not, the reality is that we live in a world where miracles do happen. We must never underestimate the human body’s will to survive. It is not our job to make the decision on who lives or dies.

Tom and Pam went on to make a full recovery, despite fire chiefs initially declaring the fire defensive and likely fatal. Now, someone’s mom and dad, brother and sister, friend and loved one, get to spend more time together and received another chance at life. We provide that hope when all else seems lost, the light in the darkness, and calm to the chaos.

Closing Thoughts

There is no magic formula to calculate risk or way to eliminate it from our profession. Risk can only be minimized through our training, physical fitness, education, mindset, and experience.

“It is our Duty to Occupy any Searchable Space with a Balance of Rapidity and Thoroughness. Making Primary Search the Most Difficult and Essential Task Performed on the Fire Scene.”

-Anthony Braxton

Critics often push back on the phrase “for them,” suggesting it glorifies reckless sacrifice. But just as no soldier joins the military to die in combat, no firefighter signs up hoping to become a line-of-duty death. We train to act aggressively and decisively—because we know there will be moments when someone’s life depends entirely on our decision to act. Risk acceptance is not recklessness—it is the calculated courage to intervene when no one else can.

We cannot allow fear, flawed assessments, or bureaucratic catchphrases to dictate our actions on the fireground. Lives hang in the balance. The fire doesn’t wait, and neither should we. When seconds count, we must be the ones who move with conviction, who search with purpose, and who never forget that our presence might be the only hope someone has left.

If we truly believe in our mission, then it’s time we stop hiding behind watered-down outdated acronyms and statements such as “Risk a little to save a little, risk a lot to save a lot, and risk nothing for what is already lost”. We must demand a culture of competence, not complacency. Let’s train harder, think smarter, and speak louder when we see the fire service drifting from its roots. At the end of the day, risk is part of the job. Let’s stop pretending otherwise—and start preparing for it. Our civilians need quick and calculated decisions rooted in experience and driven by the will to save. We must always remember the ‘X’ factor and continue to place civilian lives highest on the pedestal.

Inspired by Anthony Braxton’s “How Primary is Your Search?”

Other Sources:

- Firefighter Rescue Survey

- Search Culture Facebook Page

- Data Not Drama

- Bill Carey’s Project Mayday

- Brian Brush 2023 FDIC Keynote “An Unquenchable Faith”

- Sean Duffy Searchable vs. Survivable

- Brian Olson “Why We Go Inside”

Leave a Reply